Last week, we spotlighted the San Antonio Food Bank, a lifeline that serves more than 100,000 people weekly, providing critical food relief to families facing poverty and systemic inequities.

Their work highlights an urgent reality: food insecurity remains a persistent issue in San Antonio, particularly in under-resourced neighborhoods where grocery stores are scarce, and fresh produce is hard to come by.

But what if we could pair this essential safety net with a bold, preventative solution?

Significant research released in 2023—a collaboration between Stanford University’s Natural Capital Project and the San Antonio Food Policy Council—suggests that food forests and urban farms could transform San Antonio’s response to food insecurity.

However, this research has flown under the radar for many San Antonians.

By converting vacant public lands into spaces for growing food, we could also address urban heat, flooding, and environmental inequities

Today, we’re resurfacing these findings, exploring local models like the Tamōx Talōm Food Forest and Garcia Street Urban Farm, and unpacking the evidence that food forests are more than wishful thinking—they’re practical, proven, and ready to scale.

What Food Forests and Urban Farms Can Do

Food forests and urban farms are two promising solutions for addressing food insecurity while delivering a range of environmental and community benefits.

Food forests, like Tamōx Talōm, San Antonio’s first project of its kind, are designed as low-maintenance spaces filled with edible trees and perennial plants. Featuring species such as pecans, mulberries, figs, and citrus, they provide free, healthy food to the community while requiring minimal upkeep once established.

In contrast, urban farms—like Garcia Street Urban Farm on the Eastside—focus on high-yield vegetable production while serving as educational hubs that teach residents how to grow food and engage in sustainable agriculture.

According to research released in 2023 by Stanford University’s Natural Capital Project and the San Antonio Food Policy Council, if all 16,800 acres of underutilized public land across San Antonio were converted to food forests, they could produce 192 million pounds of fruit and nuts annually, valued at over $995 million.

Alternatively, converting that land into urban farms focused on vegetables could generate 926 million pounds annually, worth more than $1.1 billion at market value.

To put this into perspective, in 2024, the San Antonio Food Bank distributed 85.8 million pounds of food across its 29-county service area over the course of an entire year. Converting portions of San Antonio’s underutilized public land to food forests and urban farms could significantly multiply that output, creating sustainable, localized food sources in areas where fresh food is hardest to access.

They could save the city an estimated $3.5 million annually in urban cooling services by reducing temperatures in vulnerable neighborhoods most impacted by extreme heat. This natural air-conditioning is particularly valuable in areas with limited green space, where concrete and asphalt can amplify temperatures by up to 15°F compared to tree-covered neighborhoods. Trees provide shade and release water vapor through evapotranspiration, which can cool the surrounding air—a single young tree has a cooling effect equivalent to 10 room-sized air conditioners running for 20 hours a day, and that benefit doubles as the tree matures.

Additionally, their deep-rooted trees and perennial plants absorb rainwater, reducing surface runoff and enhancing natural flood control. This infiltration helps mitigate flooding during heavy storms and alleviates pressure on drainage systems, particularly in neighborhoods with aging or insufficient infrastructure.

While converting all available vacant land is highly unlikely—due to competing priorities and needs like housing, recreation, and infrastructure—the research highlights the enormous potential even a fraction of this land could offer. Strategic development of food forests and urban farms, particularly in districts with the highest levels of food insecurity and underutilized space, could make a significant impact.

The How: Local Models of Success

San Antonio already offers promising examples of food forests and urban farms demonstrating the potential for urban agriculture to address food insecurity and environmental challenges.

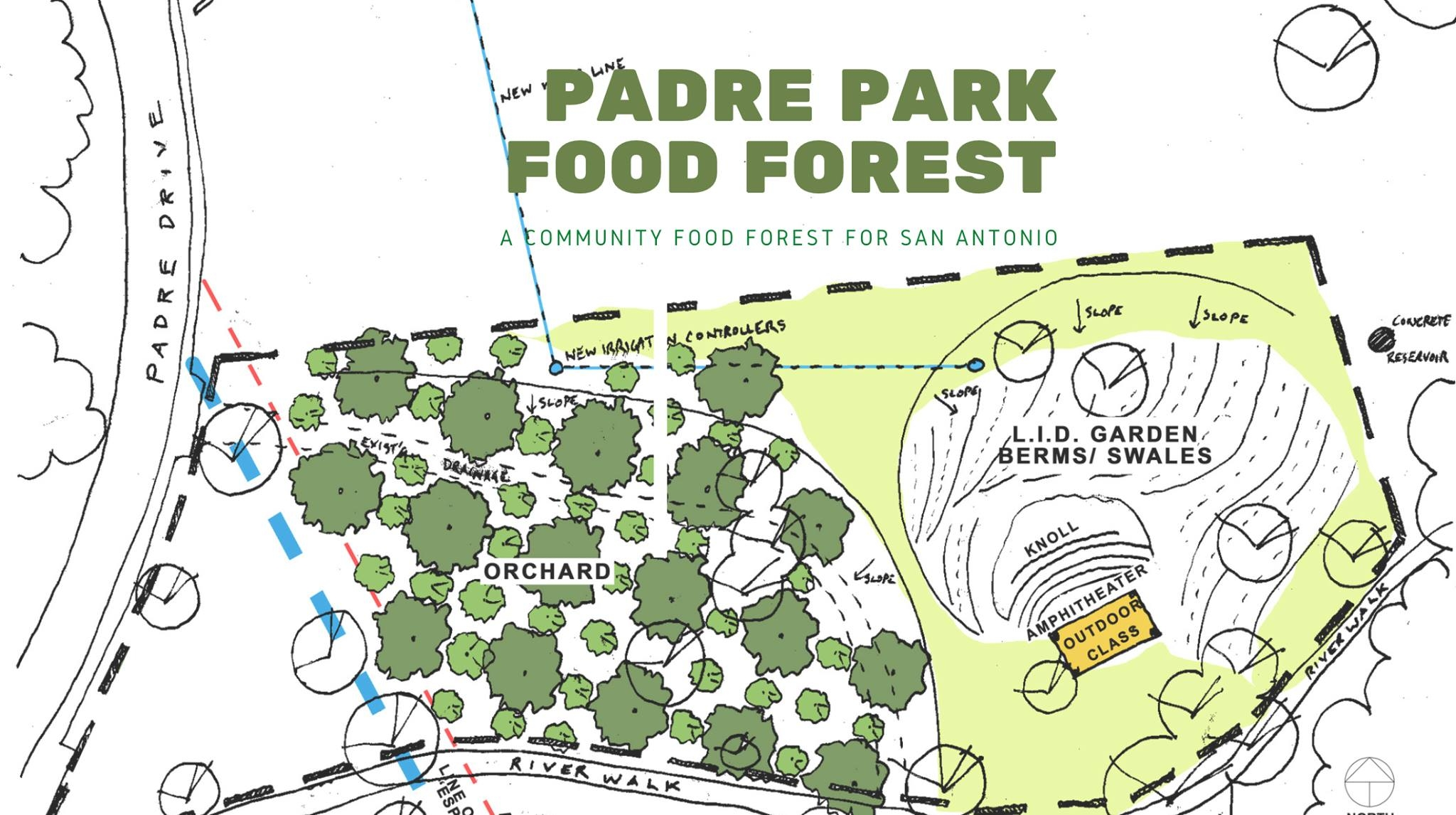

On the city’s Southside, the Tamōx Talōm Community Food Forest, planted in 2022, transformed a neglected space into a thriving orchard filled with native and edible trees like pecans, mulberries, and figs. With a modest initial investment of $25,000, Tamōx Talōm is projected to generate $87,000 worth of fresh produce annually once the trees reach maturity.

The project engages the community through weekly volunteer days, inviting residents to take ownership of the space by helping with maintenance and care. Looking ahead, partnerships with the San Antonio Food Bank aim to distribute excess harvests to households experiencing food insecurity, ensuring the forest’s benefits are widely shared.

On the Eastside, the Garcia Street Urban Farm offers a complementary approach. This 4.1-acre farm, a collaboration between Eco Centro and Opportunity Home San Antonio, provides fresh produce while serving as a hub for education and empowerment.

Beyond food production, Garcia Street runs workshops on organic farming, nutrition, and sustainable practices, teaching residents to grow food at home. By equipping the community with the skills to produce their own healthy food, the farm reduces reliance on external sources and helps build long-term food resilience in underserved neighborhoods.

Addressing the Challenges

Urban agriculture offers tremendous potential, but it isn’t without its hurdles. Resource management remains a key challenge, as food forests require consistent irrigation systems, community buy-in, and ongoing maintenance to thrive. Without proper care, early projects like the orchard at Villa Coronado Park failed to succeed, highlighting the importance of sustained stewardship.

Additionally, the use of vacant public spaces raises questions about land use trade-offs—balancing priorities like much-needed housing, recreational opportunities, green space preservation, and food production requires thoughtful planning and community input.

Existing tools and partnerships are starting to scratch the surface of these challenges. Programs like San Antonio’s Community Toolshed point in the right direction by providing essential equipment, such as tillers and trenchers, to support urban agriculture efforts. However, scaling these resources and ensuring their accessibility to all communities remains an ongoing need.

Similarly, partnerships with organizations like the San Antonio Food Policy Council offer valuable expertise and stewardship, but broader investment, education, and community buy-in are still critical to ensuring urban food systems can truly thrive and meet the city’s needs if giving a green light.

A Path Forward: Cultivating Resilience Together

Food forests and urban farms won’t solve food insecurity or urban heat overnight, and converting every vacant lot in San Antonio isn’t realistic.

However, the progress of projects like Tamōx Talōm and Garcia Street Urban Farm proves that even modest investments in urban agriculture can deliver benefits—feeding families, cooling neighborhoods, and building stronger, more connected communities.

The 2023 research offers a clear blueprint: by strategically developing underutilized land, we can tackle multiple challenges our city faces all at once.

San Antonio’s vacant lots hold more than just untapped land—they hold the promise of a greener, healthier, and more resilient city for everyone.